“Organizing is what you do before you do something,

so that when you do it, it is not all mixed up.”

(A. A. Milne)

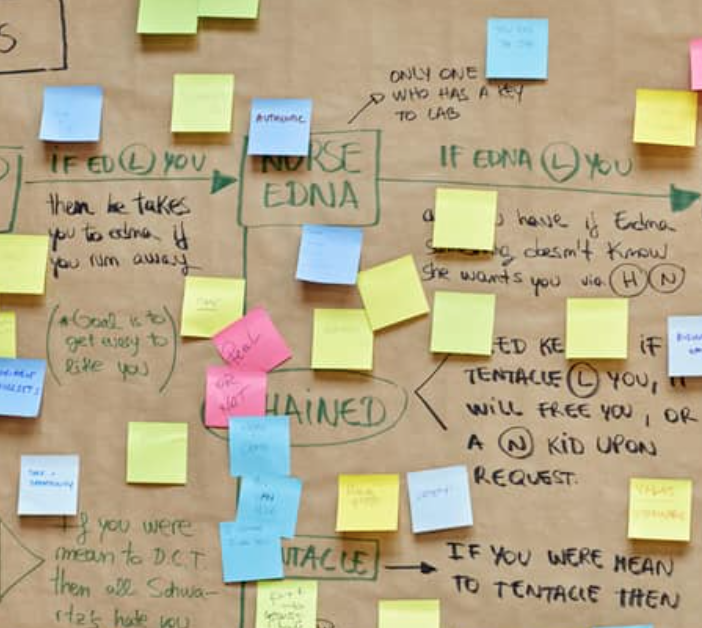

By now you know your topic, it is clear who is going to tell the story and you’ve got a mind map, an affinity diagram or just many post-its with notes that will help you give your story content. Time to start working on the storyline, the skeleton of your story. Depending on the situation and/or what you or the community has decided this phase of the process will be an individual or a collective one. But before you enter it we’d like to share with you some basic theoretical information about ‘narrative structure’.

Constructing the storyline

In every (good) story there are at least three phases: a beginning (A), a middle (B) and an end (C). Each phase has a function for the story. In A, the situation is outlined and the character or characters relevant to the story are introduced. And perhaps some more information is given to help the prospective listener follow the story. This phase is called “exposition”. In a fairy tale, it might begin with “Once upon a time, in a far away country, …”. In B, a problem, dilemma or challenge is introduced and explained how this is dealt with. In a story about Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) this might be the phase in which you explain how you got in touch with the ICH and what that has meant to you. Then, in C, you describe the message of the story, which could be an expression of happiness about the bonding function of the ICH for the community.

You can experiment with the sequence of these phases (some detective stories, for instance, start with C, then go to A, B and to C again). We recommend that you structure your story in these 3 phases and summarize the scope of your story in 3 sentences, one sentence for each phase. If working with several storylines, you do this for all storylines. In that case you also have to decide how you incorporate those into the story: as a complete story within a story and if you do that, what is their order, or do you cluster the A phases of all the storylines, and the B phases etc. This structuring and summarizing is not an easy task, but it will help you get the story right.

Adding ‘flesh to the skeleton’

Once you are happy with the storyline(s) you can start adding details, flesh, to the skeleton. But before you do, we’d like you to take notice of some theoretical information related to this.

Much research has been done on what makes a good story a good one. In the previous paragraph we already mentioned its construction in three, sometimes slightly more, phases with each a clear goal. Another characteristic of a good story appears to be that it addresses three so-called domains: the personal, the emotional and the universal domain. To start with the latter: when talking (or telling) about ICH, you could consider general or factual information about this ICH as the universal domain. If your story consisted of only this kind of information, you probably wouldn’t be able to hold the attention of your audience for very long. At least, if it’s an audience that expects to listen to a story. Adding some personal information, such as a description of your first encounter with the ICH, will undoubtedly help to keep their attention longer. By also telling them about the feelings this encounter evoked in you, you really grab their attention! Why? Because the personal information adds context to which people can relate and the emotional information allows them to feel and to emphasize with the narrator. Without this emotional component, a story loses its power of expressiveness.

Keeping this information in mind, have another look at your mind map or the like. Which details belong where in the story? Don’t write out the story yet! Just re-order all your information in such a way that for you the storyline and the content of the story become clear.

Setting up a storyboard

Before you set-up your storyboard, you have to decide about the format of your digitally shared story: just sound or sound and images? We continue as if you’ve decided on the latter option.

You’ve got the storyline(s) and have added details. Now is the time to have another look at them and start associating the details with images and sound. For instance: Does an image pop up in your mind when you think about your first awareness of the ICH? Does the moment remind you of music or a sound (like voices, ambient sounds)? Try to be as open as you possibly can and take notes. If you’re working with an affinity diagram, whether online or not, add post-its with these notes in the right spot in the storyline(s).

When you’ve added this information to your storyline, go to its beginning, close your eyes and try to imagine what the video will look like if you’d add the images? Sometimes an image says more than words. Do you have images that could replace words? Where do you think sound adds to the story? If you’re dealing with multiple storylines, would it help insert links in the main story to direct people to another storyline?

Digital storytelling at its best will use a combination of carefully chosen scenes, character(s), images and sounds or music to create a full-sensory, emotional experience.

Having done the above, ask yourself which images and sounds are already available and which you will need to produce or make. Is the outcome of this realistic? Do you have time and/or money to produce the ones missing? If not, take one step backwards and give it another thought. Also, keep in mind that if you’re using images and/or sounds that are not your own, you then have to deal with copyrights. (See also Module 5, ‘Technical aspects of digital narratives’.)

Once you have a clear sketch of the story in your mind you can start setting up the storyboard. For this you can use various digital tools like canva, storyboardthat or wonderunit (free) or download a storyboard template to work on a paper version.

Storyboarding

There are a few things you have to keep in mind when giving content to your storyboard (= storyboarding):

- There is something like a general consensus that a digitally told story should not last longer than 2 to maximum 4 minutes. An audience motivated to learn more about a specific topic might be willing to devote more time to an engaging story and in social media contexts, 30 seconds seems to be best.

- make sure there are no copyright restrictions on the images and sounds you want to use. If not using your own, look for audio, video, and images online that are in the public domain, royalty-free, or Creative Commons-licensed;

- make sure you are not ‘colouring red roses red’ when adding images or sounds to the story (meaning: story and image/sound should complement or juxtapose each other, not duplicate!);

- when using sound, make sure not to put sound with lyrics under spoken text. Be careful with lyrics anyway. They It will distract the audience;

- keep a keen eye on the rhythm of the story. Making a storyboard will help you in doing this.

And another aspect to think about is how you are going to share your story and if that implies certain restrictions. (See Module 5, ‘Technical aspects of digital narratives’.)

“The storyboard for me is the way to visualise the entire movie in advance. ”

quote: Martin Scorsese

Finally … You can start storyboarding! The more precise you do this, the more you will benefit from it when actually creating your digital story. Organizing all the information you have (narrative, images, sounds, music, links to further information or related storylines, transitions from one scene to the next etc.) in a storyboard not only allows you to find out what information might still be missing or is in need of some more attention, but it also gives other people the opportunity to gain insight into the story and respond to (aspects of) it. And this is very handy when you’re creating the digital story with several people, for instance people from the community you share the ICH with.